片岡 章雅

Website Akimasa Kataoka

研究内容

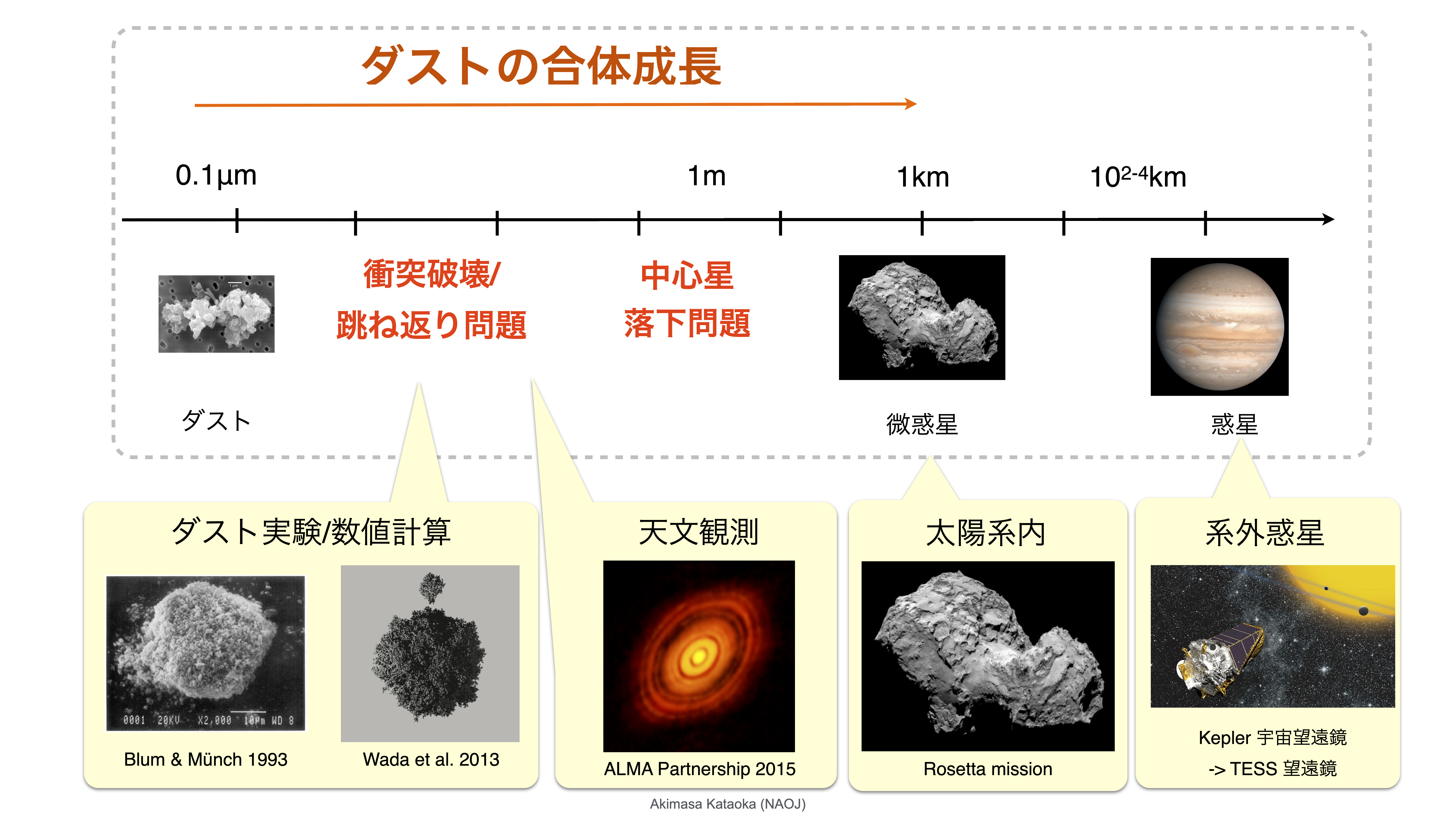

惑星形成を考える上で、最終的なゴールはなんだろうか。この回答は無数にあると思うが、私のゴールの1つは、惑星を形成する上での困難がないことを証明する、ということだと考えている(どうやって惑星を作るのか、というシンプルな問いです)。我々は地球という固体惑星に住んでおり、太陽系には数個の惑星があることがわかっており、太陽系外惑星は少なくとも数千個見つかっている現代において、惑星ができることに疑問はない。では、宇宙においてそんなに自然に惑星はできるのだろうか。ここで、惑星形成を宇宙における固体のサイズ成長と捉える。下図は、その概念図である。

惑星形成を成約する観測事実は多岐にわたる。下図はその概念図である。ここでは、惑星形成を宇宙にある固体物質のサイズ成長と捉えよう。宇宙において固体は超新星爆発やAGB星の周りで作られ、初期サイズはミクロンサイズ以下だと考えられている。このような固体物質が、若い星の周りの星周円盤に到達し、互いに衝突・付着成長を始める。しかし、放っておけば惑星ができるほど物事はそう単純ではない。ダスト実験/数値計算から、ダストの付着成長は高速衝突による破壊や跳ね返りによって阻害されることが指摘されている。理論的には1mmから1m程度のダストはガス抵抗により角運動量を失って円盤寿命より早く中心星に落ちると思われているにも関わらず、円盤の電波観測から、ミリメートルサイズのダストが豊富に存在することが指摘されている。キロメートルサイズの微惑星の太陽系外天体での検証は難しいが、太陽系に残存する微惑星の残骸と思われる小天体は探査機によって調べられ、その空隙や物質強度がわかってきている。更に、系外惑星探査によって発見された系外惑星系は、太陽系とは違ったバラエティを示している。近年、すばる・アルマ望遠鏡、ロゼッタ・はやぶさ探査機、ケプラー望遠鏡等により観測が目覚ましい発展を遂げており、それに突き動かされて理論も発展している。このように、惑星形成分野は現在非常に活発な分野である。

我々のアプローチ

我々は、ALMA望遠鏡データを用いた惑星形成理論の検証や、ダスト集合体の理論計算から太陽系天体への応用などの手法で研究しています。研究内容は日々変わっているので、例えばこちらのプレゼンファイルなどを御覧ください。

2017年以前のニュース

国立天文台理論研究部助教に着任 (2017年12月1日)

HL TauのALMA偏光観測 (2017年7月7日)

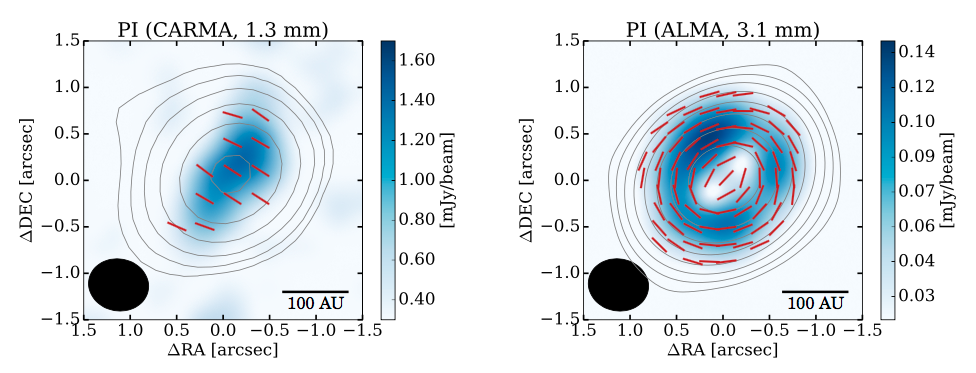

惑星は、原始惑星系円盤と呼ばれるガス円盤の中でダストが合体成長することで形成されます。そのため、成長中のダストがどのくらいの大きさを持つのかを原始惑星系円盤の観測から制限することができれば惑星形成理論を発展させることができます。我々は、2015年に原始惑星系円盤のミリ波偏光観測を用いると散乱起因の偏光を受けることができ、そこからダストのサイズを測れるという理論を提唱していました。今回我々は、HL Tauという惑星が作ったと見られるリング状の放射が確認されている原始惑星系円盤のALMA偏光観測を行いました。その結果、ミリ波の偏光は従来思われていたような磁場によるダスト整列ではなく、輻射場によるダスト整列と、我々の提唱していた散乱起因の2つが組み合わさって起こっていることがわかりました。また、散乱由来の偏光成分の解析から、成長中のダストサイズは100ミクロン程度であることがわかりました。

arXiv

国立天文台フェローとして国立天文台理論研究部に着任 (2017年4月1日)

身分がHumboldt Research Fellowに変更(2016年12月1日)

日本学術振興会海外特別研究員としてドイツ・ハイデルベルク大学に着任 (2015年4月1日)

受賞: 総合研究大学院大学 長倉研究奨励賞を受賞 (2015年3月24日)

詳しくは理論研究部ニュース及び長倉研究奨励賞ホームページをご覧ください。博士号を取得 (2014年9月30日)

博士論文"Planetesimal Formation via Fluffy Dust aggregates"が受理され、総合研究大学院大学より博士号を取得。

国立天文台理論研究部にて

受賞: 総合研究大学院大学H26年度学長賞受賞 (2014年4月7日)

総合研究大学院大学H26年度学長賞を受賞しました。

祖父と。総研大葉山キャンパスにて。

受賞: 日本惑星科学会最優秀発表賞を受賞 (2013年11月21日)

日本惑星科学会2013年秋季講演会にて、最優秀発表賞を受賞しました。詳しくは理論研究部ニュース及び惑星科学会ホームページをご覧ください。

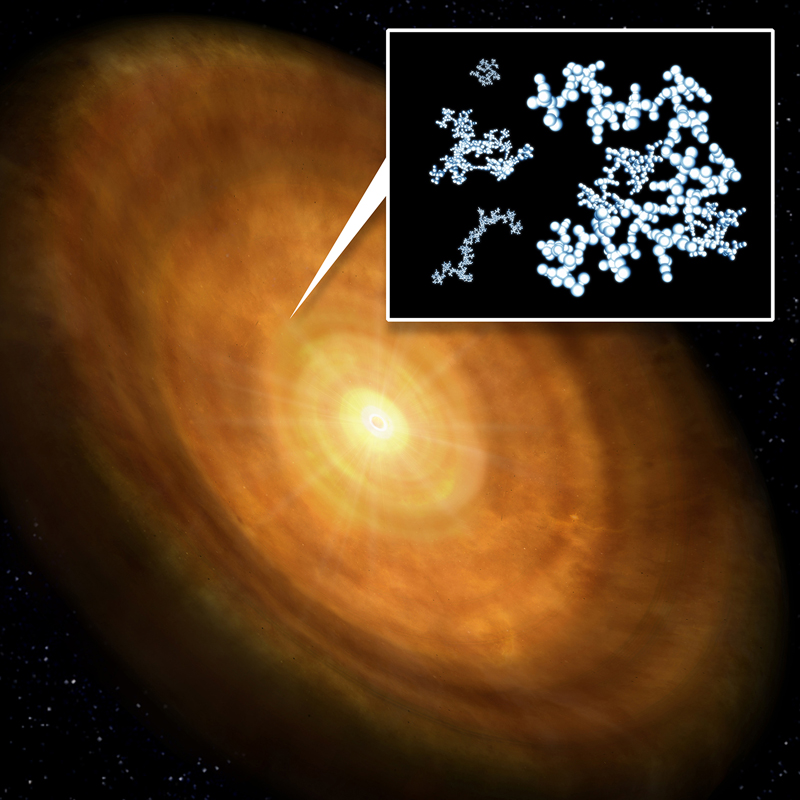

プレスリリース「惑星の種はすき間だらけ」 (2013年10月4日)

最新の研究内容に基づき、プレスリリースを行いました。詳しくはプレスリリース をご覧ください。

論文: 高空隙ダストを経由することで微惑星形成過程を解明:

本論文は再び A&A highlighted paper に選ばれました。 (2013年8月14日)

See the highlighted papers of A&A for more details.

It has been a long-standing puzzle that millimeter- to meter-sized grains tend to drift very rapidly towards their parent star, particularly with observational evidence that these grains are present in circumstellar disks more or less independently of their age. The fact that these grains may be porous and not compact and would thus drift much more slowly has been advocated as a possible solution. Nevertheless, the puzzle has remained unsolved because asteroids and comets with a very low porosity (down to a density of 0.00001 g/cm^3!) have never been observed. The authors propose a way around this and show that grains should first grow by becoming extremely porous before being compacted by gas drag and then by self-gravity. This model can account for the observed population of comets and their comparatively high densities (about 0.1 to 1 g/cm3) by assuming that they are the remnants of planetesimals of sizes of order 10 km and beyond.

論文: 高空隙ダストアグリゲイトの静的圧縮強度

最新の論文が A&A highlighted paper に選ばれました。 (2013年5月28日)

See the highlighted papers of A&A for more details.

Understanding the structure and growth of ice particules in circumstellar disks is key in analyzing observations of these disks and inferring the consequences for planet formation. Grains had been considered spherical and compact, with a density equal to that of ice, i.e. about 1 g/cm3, until recent work has pointed out that growth tends to form fluffy, very fluffy aggregates with densities as low as 0.00001 g/cm3 and planetesimal sizes. However, no such objects have been observed today, and it is thus critical to understand how we can transform fluffy aggregates into (relatively) dense planetesimals. The work by Kataoka et al. is a first step in that direction: Using numerical experiments they derive a relation between the pressure that is applied to the aggregates (e.g., due to gas drag in the disk) and their filling factor (i.e., their physical density). They show that the filling factor is equal to the size of the monomers forming the aggregates multiplied by the cube root of the ratio of the pressure that is applied to the roll energy of the monomers. This relation will be crucial for understanding the history of the evolution of grains and planetesimals in disks.